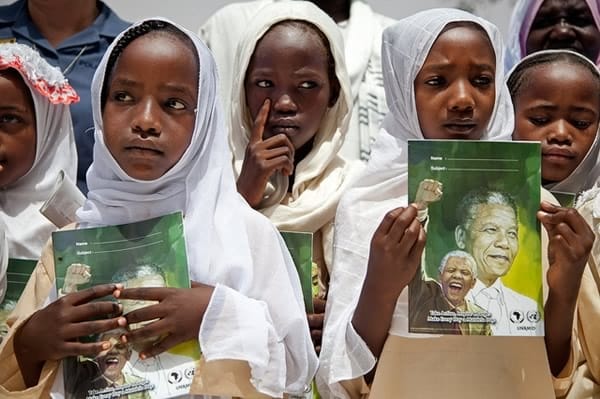

"A good head and a good heart are a formidable combination." − Nelson Mandela

When we are directly confronted with another person's pain, particularly a small child's, we are instantly compelled to help even though the circumstances may be much less dire than those experienced every day by people living in extreme poverty. Our desire to help is almost automatic − we can't maintain our self-image without helping − we are generous, caring people.

Despite the generosity of human nature, it is relatively easier to push out of our minds the needless suffering among the world's poorest people; we don't have to think about it.

My best friend is one of the most compassionate people I have ever met. She is an advocate for the lowest paid workers in the large company she helps manage, heads the foundation for her children's school despite an extremely busy schedule, and has an adopted child along with two biological children of her own. When we walk down the street and she sees a homeless family, she has to give them money. When she sees pictures of orphans she says, "How can I resist helping?" But when I talk with her about extreme poverty and preventable death and misery she experiences it as an abstraction.

Most of the time we deny what we don't experience firsthand−the prevalence of preventable life-threatening illness, premature death, and misery−and we, therefore, do nothing. When we do think about it, we make great excuses for not helping; we tell ourselves the money won't really reach the people who need it, that we should work for structural change not 'band-aids,' that environmental disaster is looming, or that there are too many people to help. Yet, the reality is that effective charities use your donations to make a measured difference−a real impact. They reduce suffering, cure blindness (SEVA and Fred Hollows), restore an ostracized young woman's health and bring her back into her community (Fistula Foundation), and prevent premature death (Against Malaria Foundation). None of our charities prevent a continued response to environmental disaster or much-needed structural economic and social change. Evidence also suggests that as we raise a community’s standard of living, population growth is effectively curbed.

Another significant factor that prevents most of us from giving more is our need to fulfill our own irrational material desires. The story below is a charming, touching illustration of this phenomenon within our culture. (I confess to the fact that my son is a farmer)…

One day the father of a very wealthy family took his son on a trip to the country with the express purpose of showing him how poor people live. They spent a couple of days and nights on the farm of what the father considered a very poor family (not extreme poverty). On their return from the trip, the father asked his son, "How was the trip?"

"It was great, Dad," said the son.

"Did you see how poor people live," the father asked.

"Oh yeah," said the son.

"So tell me what did you learn from this trip," the father asked. The son answered, "I saw that we have one dog and they have four. We have a pool that reaches from the middle of our garden and they have a creek that has no end. We have imported lanterns in our garden and they have stars at night. Our patio reaches to the front yard and they have the whole horizon. We have a small piece of land to live on and they have fields that go beyond our sight. We have servants to serve us. But they serve others. We buy our food, but they grow theirs. We have walls around our property to protect us, but they have friends to protect them."

The boy's father was speechless, then his son added, "Thanks Dad for showing me how poor we are."

As we approach 2014, it would be great if we could shed our excuses for not helping those living in extreme poverty. We could look at all those 'necessities' that are actually luxuries, and reduce our consumption of them by a significant percentage. We could then determine how much money this would save and commit to donating all of it to our effective charities. From personal experience, I know how difficult it is to make extreme poverty concrete and to become more generous, but I want to make 2014 a 'personal best year' for myself.

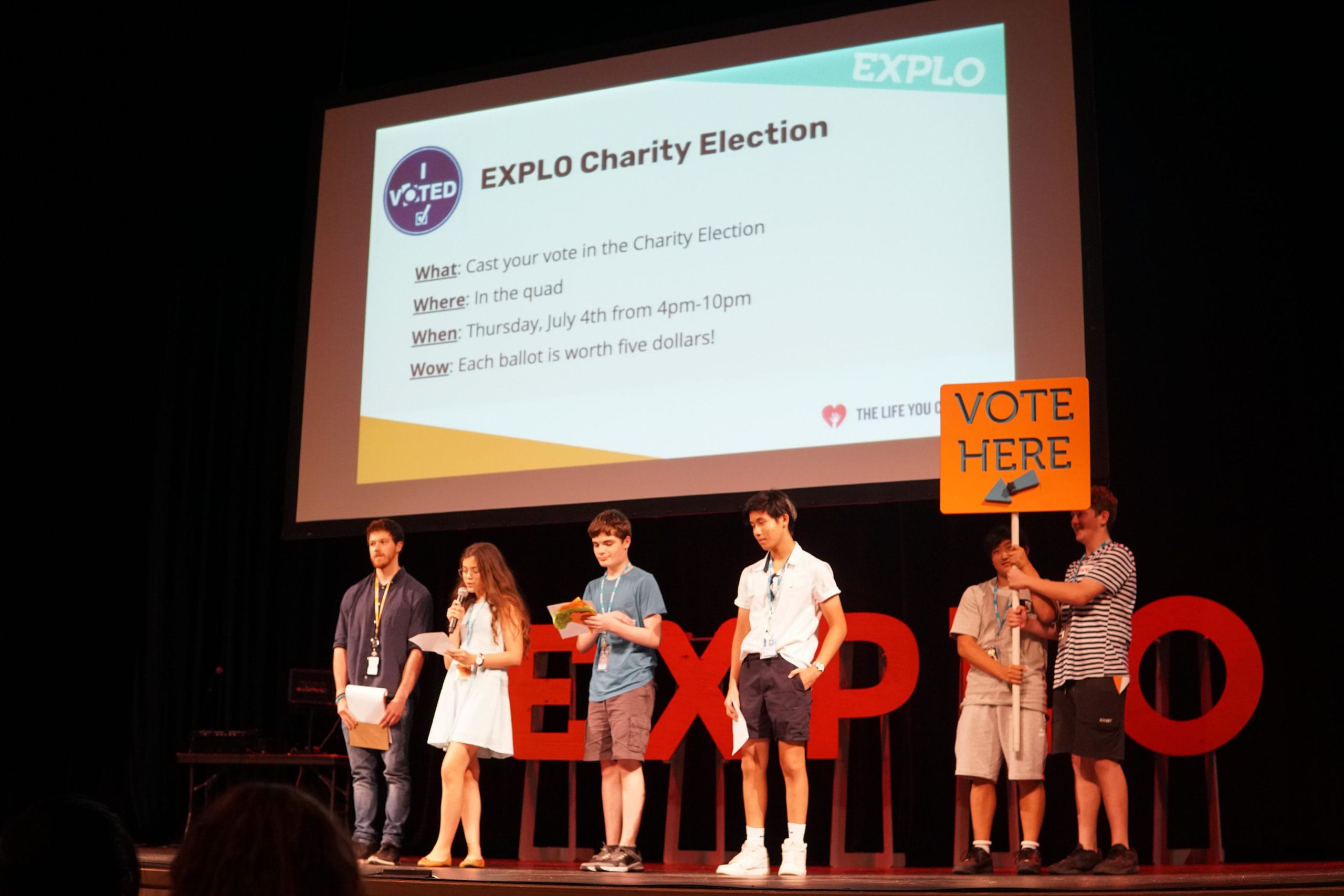

Won't you join me? Let's make it a happy new year, not only for ourselves and our loved ones, but for those who could truly use our support.

Thanks so much in advance for your help,

Charlie