“IPA recently completed a large-scale randomized study for Living Goods showing the model is reducing child deaths by a staggering 27 percent. The result has been nothing short of transformational. The power and quality of research has persuaded policymakers, replication partners, and major funders to back a rapid scale up of the approach. As a result, Living Goods’ reach has tripled to 5 million people served. Proof positive that IPA’s research can lead to disruptive change for those most in need.” –Chuck Slaughter, Founder of Living Goods

Here is IPA’s summary of the study

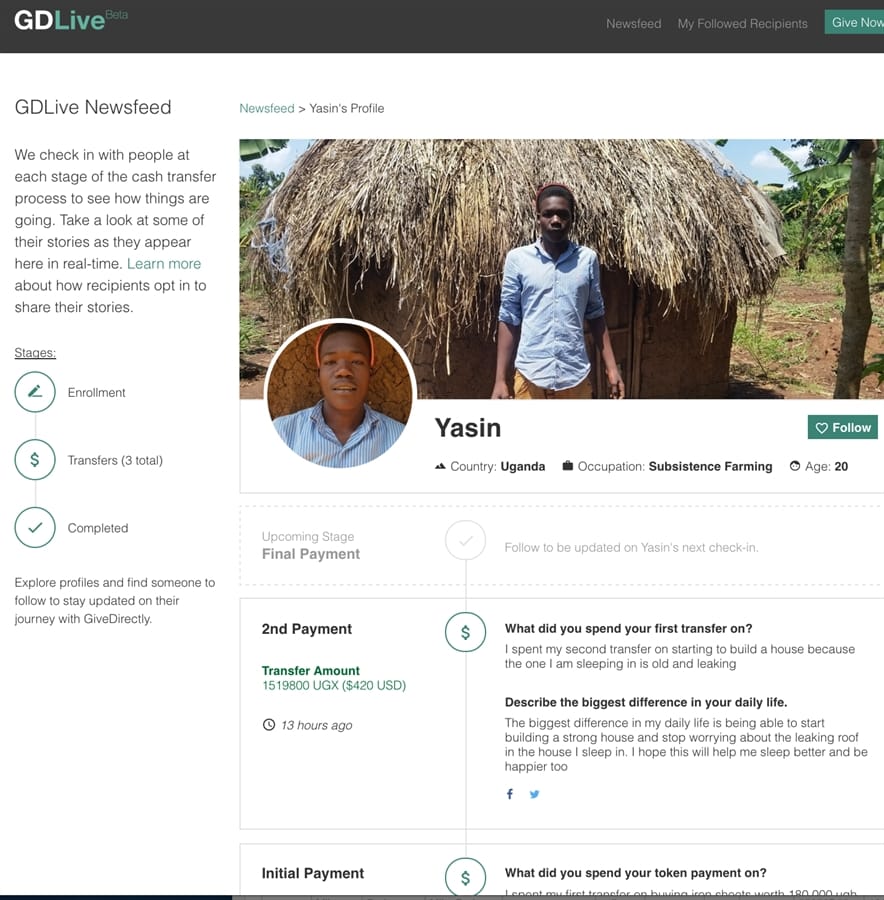

An Entrepreneurial Model of Community Health Delivery in Uganda

Despite a substantial decline in child mortality in recent years, millions of children still die from preventable diseases every year. In this study in rural Uganda, researchers evaluated the impact of a micro-franchise model, which incentivizes door-to-door community health workers. The program reduced mortality among infants and children, improved knowledge about health among clients, and increased the visits that households received from health workers.

Policy Issue

Despite improvements in under-five child mortality, an estimated 5.9 million children worldwide died in 2015; more than half of these deaths were due to conditions that could have been prevented or treated with simple, affordable interventions.1 A majority of these deaths occurred in the poorest countries in the world, among people with inadequate access to basic health services. An increasingly common approach to reaching these populations is community health worker programs, which aim to improve health outcomes by recruiting community members to connect healthcare consumers and providers.2

However, evidence indicates that this approach has mixed success in reducing child mortality.3 For example, weak incentives for community health workers to deliver timely and appropriate services may limit the effectiveness of these programs.4 Micro-franchise models in which health workers earn a margin on product sales as well as small performance-based incentives could address these challenges, improving service delivery and health outcomes. Researchers assessed the impact of this entrepreneurial model of community health delivery in Uganda.

Context of the Evaluation

Although infant and under-five deaths in Uganda have declined substantially in recent years, 69 out of 1,000 children in the country died before age five in 2012.5

Two NGOs—Living Goods based in the United States and BRAC based in Bangladesh—created a community health worker program with the aim of improving access to and adoption of simple, proven health interventions among low-income households in Uganda. Through the program, the organizations recruit, train, equip, and manage Community Health Promoters (CHPs) who go door-to-door educating families on key health behaviors and distributing impactful and affordable products. In addition to providing health education and access to basic health products for low-income households, this model aims to create sustainable livelihoods for the CHPs, who can earn an income through profits from product sales and small, performance-based incentives for visiting households with pregnant women and newborn children.

Details of the Intervention

Researchers worked with Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) to carry out a randomized evaluation to assess the impact of the Living Goods and BRAC Community Health Promoters program on access to health services and child health outcomes in rural Uganda. Among 214 rural villages across 10 districts, researchers randomly assigned 115 villages to the treatment group, which received the CHP program, and 99 villages to the comparison group, which did not receive the program.

Qualified CHPs were selected through a competitive application process in each treatment village, and trained for two weeks in health and business skills. Over a three-year period, these CHPs conducted home visits in treatment villages, educating households on essential health behaviors, providing basic medical advice and referrals for more serious diagnoses, and selling discounted preventive and curative health products. CHPs purchased these products directly from Living Goods or BRAC branches at an even lower price, allowing them to earn a profit on each product sold. Additionally, in order to incentivize the CHPs to provide maternal, newborn, and child health services, the program paid them an additional financial incentive for home visits to pregnant women and newborns.

Results and Policy Lessons

The Living Goods and BRAC CHP program increased the number of visits that CHPs paid to treatment group households, improved health knowledge and behaviors, and reduced mortality among children.

The program improved households’ access to healthcare services by increasing the number of CHP visits. Twenty-four percent of households in the treatment group reported having been visited by a CHP in the previous month, compared to five percent of households in the comparison group. Households with newborn or young children were even more likely to receive a visit; treatment households with a newborn baby were 71 percent more likely to have received a follow-up visit in the first week after birth.

The CHP program also improved health knowledge. Households in the treatment group were 11 percent more likely to know that diarrhea is transmitted by drinking untreated water (relative to 37 percent of people in the comparison group); 16 percent more likely to know that zinc is effective in treating diarrhea (relative to 23 percent in the comparison group); and 39 percent more likely to know that mosquito bites are the only cause of malaria (relative to 7 percent in the comparison group.)

Health-promoting behaviors also improved. Households in the treatment group were 5 percent more likely to have treated their water before use, relative to 77 percent in the comparison group, and their children were 13 percent more likely to have slept under an insecticide-treated bed net, relative to 40 percent in the comparison group.

Ultimately, the program reduced under-5 child mortality by 27 percent and infant (under-1) mortality by 33 percent, relative to the comparison group.6 It also reduced neonatal mortality by 27 percent, on a base of 27.8 deaths during the first month of life per 1000 live births.

This study suggests that micro-franchise models can effectively provide community health providers with incentives to increase access to low-cost health products and basic newborn and child health services to low-income families. IPA is working with researchers to replicate the study, and based on the results of this evaluation, the Living Goods and BRAC CHP program will be scaled up to reach an estimated 6.6 people by 2018 (5.3 million individuals in Uganda and 1.3 million in Kenya).

Read more about the study in this blog post, and how it is being scaled up in this impact case study.

Sources

[1] WHO. 2016. “Children: reducing mortality.” Last modified September. Accessed October 7, 2016. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs178/en/

[2] Witmer, Anne, Sarena D. Seifer, Leonard Finocchio, Jodi Leslie, and Edward H. O’Neil. 1995. “Community health workers: integral members of the health care work force.” American Journal of Public Health 85.(8_Pt_1):1055-1058.

[3] Lewin, Simon, Susan Munabi-Babigumira, Claire Glenton, Karen Daniels, Xavier Bosch-Capblanch, Brian E. van Wyk, Jan Odgaard-Jensen, Godwin N. Aja, Merrick Zwarenstein, and Inger B. Scheel. 2010.. “Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases.” Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3.

[4] USAID. 2012. “Community and Formal Health System Support for Enhanced Community Health Worker Performance: A U.S. Government Evidence Summit” Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation..

[5] UNICEF. 2013. “Information by Country: Uganda.” Last updated December 31. Accessed October 7, 2016. http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/uganda_statistics.html

[6] Researchers measured under-5 and infant (under-1) mortality as mortality rate per 1000 years of exposure to the risk of death during the evaluation. The number of months of exposure is defined as the difference between the birth date of the child, or the start date of the trial if the child was born before that date, and the date that the child turned five (one for infant mortality) if that occurred during the trial period, or the date of the endline household survey if the child was less than five (one) years old at that time, or the date of the death of the child.