For today’s blog post, I’ve asked four researchers and educators to discuss the pros and cons of our Giving Games philanthropy outreach model. Each of these academics has facilitated Giving Games for their students in their roles as teachers and mentors.

This post will share the feedback we’ve gotten from this uniquely qualified group of Giving Games facilitators. In addition to being experienced educators, each of these professors has specifically taught philanthropy through a program run by the Learning by Giving Foundation. In these semester-long college courses, students are given a $10,000 grant, which they allocate to one or more charities in their local community.

We place a great deal of weight on the feedback we receive from our Giving Games facilitators. After all, they have a firsthand view of how participants respond to Giving Games. Are participants engaged in the conversation? Are they thinking critically about the questions at hand? Which issues did they find most important?

I asked each of the Learning by Giving professors we’ve worked with to offer their thoughts—both positive and negative—on the Giving Game model. Here’s what they had to say.

Walter G. Friedrich Professor of American Literature at Valparaiso University

I teach a semester-long course on American literature and philanthropy that features a significant giving experience, but I have found Giving Games are incredibly efficient and effective in getting participants to begin developing the habits of thoughtful philanthropy.

I have had the opportunity to participate in Giving Games in two very different settings: the first was an hour-long game with a group of student philanthropy chairs from campus fraternities and sororities, while the second was a “drop-by” game for high school students attending a Future Business Leaders of America conference. In spite of these differences, both events shared a couple of notable features.

First, I noticed that even at the university-level, most of the participants had never heard of the highly effective non-profits that they were considering. So these games were very successful in getting the word out about these organizations and their causes. This is critical for widening the circle of charitable concern.

Second, in spite of the fact that participants knew that they were playing a “game,” each of them took the task of selecting a charity very seriously. Even the high school students, who only had a few minutes between conference sessions to make their choice, read the material closely and weighed their decision with care. In an age of text message giving and viral social media campaigns, this degree of discernment was inspiring.

Chair and Associate Professor in the Department of Public Administration at SUNY—Binghamton

I have taught courses in experiential philanthropy at Binghamton University since 2009. These courses provide students with the opportunity to make grants to nonprofit organizations in the Greater Binghamton community.

I have taught courses in experiential philanthropy at Binghamton University since 2009. These courses provide students with the opportunity to make grants to nonprofit organizations in the Greater Binghamton community.

The goal of these courses is to get students to reflect on the role philanthropy plays in their lives, both currently and in the future. These courses are systematic in orientation and, I hope, engage students in deep reflection about civic contributions, how they make a difference and what it takes to do philanthropy well. Students find the process enriching, but at times frustrating, due to the difficult questions effective giving raises for them.

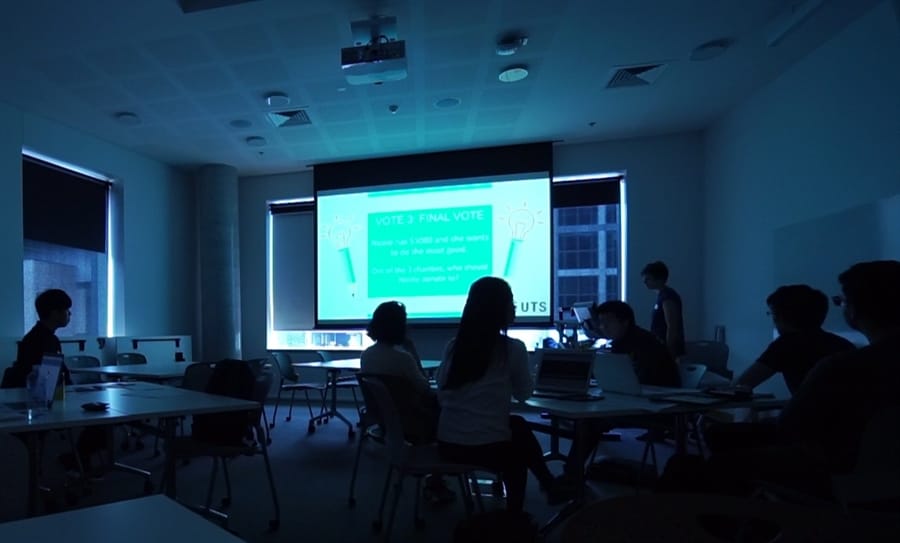

This past school year, I facilitated a Giving Game with a group of students living in Binghamton University’s Public Service Learning Community. In the absence of a full course, the Giving Games introduced students to the challenge of effective philanthropy. Over four one-hour sessions, students discussed questions about their views toward charitable giving: What are their core values? How do they apply those core values to their decisions to give time or money? How do they evaluate opportunities to give time or money? How do they compare charitable organizations? How do they evaluate giving locally versus internationally?

The most rewarding part about facilitating a Giving Game was seeing the passion for effective giving it inspired in these students. All of the students had chosen to live in a community committed to public service; at the same time, few had reflected on the range of ways in which they could make a difference and how to evaluate those options effectively. My impression is that after the Giving Game, these students realized that altruism and making a difference was more complicated than they had thought. Effective giving involves unexpected trade-offs and assessment of competing values. Most important, the Giving Game introduced students to the value of effective philanthropy and has led some to take service learning and other courses focused on public service. In that way, the Giving Game made a valuable contribution to the university’s effort to prepare students for lives of active citizenship.

Founding Director of The Social Impact Lab at Northeastern University

Author and instructor of the MOOC Giving With Purpose

Giving Games have complemented my experiential philanthropy courses at Northeastern University in several ways. My students run Giving Games that are open to the whole campus, so they build their organizational, marketing, and facilitation skills while introducing a wider audience to the significance of giving as a lever for social change. The student facilitators draw on Giving Games’ content library for ideas and models, but they also incorporate their own knowledge and insights from my course.

Giving Games have complemented my experiential philanthropy courses at Northeastern University in several ways. My students run Giving Games that are open to the whole campus, so they build their organizational, marketing, and facilitation skills while introducing a wider audience to the significance of giving as a lever for social change. The student facilitators draw on Giving Games’ content library for ideas and models, but they also incorporate their own knowledge and insights from my course.

I have found that students who conduct Giving Games often become even more thoughtfully engaged in our course’s grant making process because they have had to teach their peers abut the importance of striking a balance between their passion to make a difference and the value of critical thinking and objectivity when allocating limited resources to nonprofit organizations. The students who participate in Giving Games may never take my course, but they get an intense snapshot of the intellectual, social, ethical, and financial questions my students grapple with throughout the semester. Those are powerful experiences for an activity that is relatively easy to plan and implement.

Professor of Sociology at Framingham State University

Learning how to give well may seem like an exercise in converting theory into practice. But in truth, I’ve found that the learning comes mostly from doing. The past four years I’ve taught an experiential philanthropy course supported by a foundation grant. Over this time, I’ve seen that students must get their hands dirty in order to know what it means to be effective at giving. For the last two of these years, my students have been fortunate to have gotten the opportunity to do this, via Giving Games, long before they did so with the foundation’s money.

Learning how to give well may seem like an exercise in converting theory into practice. But in truth, I’ve found that the learning comes mostly from doing. The past four years I’ve taught an experiential philanthropy course supported by a foundation grant. Over this time, I’ve seen that students must get their hands dirty in order to know what it means to be effective at giving. For the last two of these years, my students have been fortunate to have gotten the opportunity to do this, via Giving Games, long before they did so with the foundation’s money.

Giving Games work well because they are a quick and easy way for students to become familiar with the practice of giving. In just an hour’s time, they learn a bit about two previously unfamiliar organizations addressing significant problems in the developing world. The students work in groups to come up with criteria for weighing these organizations’ effectiveness in offering remedies, and consult with sites like GiveWell that rate these organizations on a variety of measures. These Giving Games offer students a good first take at learning by giving prior to engaging in their own, more elaborate process of vetting nonprofits’ deservedness for funding.