Think of your favourite effective charity. Now imagine that they reported overhead costs (admin, salaries, etc.) of 40% or more. Would you still hold them in such high regard?

If not, you may have fallen victim to the overhead myth. For a long time, overheads, or the portion of funds used on operating costs, have taken centre stage in the evaluation of nonprofit efficiency and effectiveness. Recently this notion has been dragged out and put under scrutiny, and it's not faring well.

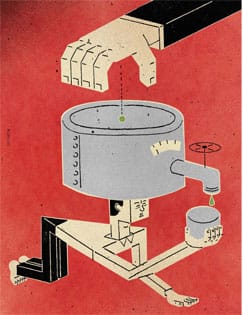

One of the main problems with placing a high emphasis on overheads is that it rewards charities for how little they spend, rather than how much they do. Organisations must invest in systems development and infrastructure to scale quickly if they wish to succeed, and nonprofits are no exception. But very few are able to get away with this kind of strategic investment, as it would greatly increase their overheads. The donating public and grant makers would respond negatively, funding would dry up, and the organisation would fold.

This is exactly what happened to Dan Pallotta, who gave the TED Talk that arguably brought this conversation into the limelight. Dan ran two charities, AIDSRides and Breast Cancer 3-Days, which raised $236 million for HIV/AIDS and $333 million for breast cancer respectively, and both collapsed when news spread that they had 40% overheads. In response, Dan launched the Charity Defence Council, an organisation to look out for the well-being of the sector at large, and whose first port of call is a campaign to clean up that dirty word, 'overheads'.

Shortly after Dan Pallotta's talk, three of the leading sources of nonprofit information in America, the BBB Wise Giving Alliance, Guidestar, and Charity Navigator, launched an initiative called The Overhead Myth, striking out against overheads as a measure of nonprofit performance with an open letter to the donors of America. In the letter they echo the need for nonprofit organisations to spend more, not less, on overheads, empowering them to use business practices to scale and achieve greater impact.

The letter also makes reference to a now-famous report in the nonprofit sector, Stanford Social Innovation Review's study of a phenomenon they call the 'nonprofit starvation cycle'. This is a vicious cycle that starts with funders' unrealistic expectations of minimal overheads in nonprofit organisations. This expectation is written into grants and leads the demands of the donating public, forcing organisations to spend their time chasing pennies, losing good talent and settling for sub-par infrastructure in the name of austerity. This extreme frugality in turn strengthens the misconception of whispy overheads, and places even more stress on the cash-strapped nonprofit, eventually starving it to cessation. Worse, in order to secure the goodwill of the public, many charities are now claiming that 100% of donations directly fund projects, with their marginal admin costs entirely covered by patchy institutional grants. Not only does this encourage the mythical non-existence of normal overheads, but also forces charities to segment funds on arbitrary terms rather than by where money is actually needed, pumping cash into leaky programs that could be made more efficient with a little administrative investment.

The result is that commonplace practices in business, like leadership development, infrastructure investment, and effective management have become heresy in the nonprofit sector. This needs to change. Of course, charities must still be held to account. Best Charities do not operate in a competitive market, instead living or dying by the willingness of the donating public and various institutions to fund them. It is therefore up to us to demand that our money is being used in the most effective way possible, to do the most good. So let's insist on high impact solutions, on absolute transparency and efficient governance. But leave overheads out of it.

What do you think? Is there too much importance placed on low overheads, or are nonprofits too different an animal for business logic to apply? Let us know in the comments below.